A journey is a person in itself; no two are alike. And all plans, safeguards, policing, and coercion are fruitless. We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.

– John Steinbeck, “Travels With Charley”

Dear Reader:

Roadside attractions tend to blur in our minds after three months of driving. To refresh our memory and to devise something like a table of contents, or table of content, this is a listing of most of the places we visited from California all the way to, uh, California. (At right, Kenny and Margo, in Oberlin, Ohio. Below, Lynn studies history at the Oregon beach where Lewis and Clark found the Pacific Ocean.)

We tagged most of these thumbnail items with the title of the article. If more than one refers to the same article, we put the tag at the end of the string.

We tagged most of these thumbnail items with the title of the article. If more than one refers to the same article, we put the tag at the end of the string.You can read individual reports by checking the “Blog Archive” column on the right side of this page. Or you can go to the search box on the upper left and write a word, such as “Havasu,” and a click will send you to the report entitled “A Tale of Two Cities.”

Speaking of cities, at the end of this report is a list of the cities on our circuit around most of the country. In a separate report, "What We Learned," we got into the practical side of our journey. It list the friends and relations we visited as well as campgrounds and motels where we stayed.

If you have questions: ludstadt2009@gmail.com

Thanks for joining us in this adventure.

A Dogged Journey

(In order of appearance, West to East and back again)

The Sundial Bridge, Redding, Calif.: In a riverside park in a city with ambitions to attract tourists, strollers can cross the spectacular o

ne-tower suspension bridge (at right) that anchors the Turtle Bay Park project on the broad but surprisingly fast Sacramento River.

ne-tower suspension bridge (at right) that anchors the Turtle Bay Park project on the broad but surprisingly fast Sacramento River.(See “Seeking the Yreka Bakery in a Toyota,” Sept. 24)

Crater Lake, near Medford, Ore. (National Park): The water reflected

the blue of the sky as we shivered a cold blue breeze. We needed the park brochure to remind us that the lake (at left, with Margo) goes down 2,000 feet, deepest in the U.S. (Its average depth is third deepest in the world.) But, like the Grand Canyon, the beautiful scene is as quiescent as a painting. We kept going.

the blue of the sky as we shivered a cold blue breeze. We needed the park brochure to remind us that the lake (at left, with Margo) goes down 2,000 feet, deepest in the U.S. (Its average depth is third deepest in the world.) But, like the Grand Canyon, the beautiful scene is as quiescent as a painting. We kept going.(See “Rogues,” Sept. 21)

Dee Wright Observatory, Willamette National Forest (State Route 42, McKenzie Pass, Ore.): Despite the name, it’s not for stargazing. The tower of rocks is built on an ancient river of lava. Apertures in the walls allow you to see the Three Sisters and other peaks.

(See “Roadside Distractions,” Sept. 22)

Ida Ludlow’s home, McKenzie Bridge, Ore.: We searched for

the home of Lynn’s grandmother. The nearby Forest Service camp is a gem of large sites by the lovely river (at right).

the home of Lynn’s grandmother. The nearby Forest Service camp is a gem of large sites by the lovely river (at right).(See “The Land of Aasland,” Sept. 24)

Kennedy School, Portland, Ore.: An amazing demonstration of imaginative reuse of buildings otherwise threatened by the demolition ball.

City of Books, Powell’s Books, Portland: It’s so big that Lynn got lost. Powell’s sells 4 million books a year. Susan Sontag called it “the best bookstore in the English-speaking world.”

Chapman School, Portland: The inside of its chimney becomes a roost for thousands of swifts every September.

Glenwood Community Church, Vancouver, Wash.: Rev. Richard Schwab, Lynn’s uncle, was the pastor. Now retired, he is still active in Bible study and scholarship. Sunday attendance: About 1,400 in two services.

(For all four, see "The City of Books,” Sept. 27)

Fort Stevens State Park, near Astoria, Ore.: From the Civil War to the start of the Cold War, it was an Army base at the mouth of the Columbia. It could have become an industrial park or a seaside city, but the state of Oregon stepped in to change the swords of defense into the plowshares of…camping. It has more than 3,700 acres, nine miles of bike trails, six miles of hiking paths, three lakes, miles of beaches and, for us, our pick of more than 500 campsites. Then the minivan’s side door wouldn’t shut. Dang.

Fort Stevens State Park, near Astoria, Ore.: From the Civil War to the start of the Cold War, it was an Army base at the mouth of the Columbia. It could have become an industrial park or a seaside city, but the state of Oregon stepped in to change the swords of defense into the plowshares of…camping. It has more than 3,700 acres, nine miles of bike trails, six miles of hiking paths, three lakes, miles of beaches and, for us, our pick of more than 500 campsites. Then the minivan’s side door wouldn’t shut. Dang.Astoria Column, atop Coxcomb Hill in Astoria, Ore.: Climbing 164 spiral steps inside a Trajan-type column bedecked on the outside with murals, we stood on the observation deck to gaze west at the mouth of the Columbia River (“the graveyard of the Pacific”) from the South Jetty at Fort Stevens State Park to Cape Disappointment. To the east, we saw the panorama of the cities of Astoria and Warrenton, the Cascade Range in the distance and the Astoria-Megler Bridge (at 4 miles over the river, it’s the longest truss bridge in the nation). An unexpected treat.

Fort Clatsop (National Parks), near Astoria, Ore.: An adroit reproduction of the little fort that housed Lewis and Clark and the Corp of Discovery in 106 days of unending rain in 1805.

(For these three, see “Graffiti,” Sept. 28)

Columbia River Maritime Museum, Astoria, Ore.: No hard rains or ocean spray hit us when we boarded the Columbia, the last seagoing lightship on the Pacific Coast. It is now on permanent exhibit, berthed at the museum. With seven galleries and narratives about the great river’s shipwrecks, salmon and sailing vessels, the nonprofit museum is one of the best we visited.

(Unblogged)

7th Street Theatre, Hoquiam, Wash.: The grand old movie house, a temple of entertainment

when built in 1928, is being restored for drama, concerts, and old movies. It’s also a demonstration of what volunteers can do to preserve our past.

when built in 1928, is being restored for drama, concerts, and old movies. It’s also a demonstration of what volunteers can do to preserve our past.Olympic National Forest (National Park, National Forest) Forks, Wash.: It was raining in the rainforest.

(For both, see “Rolling Minivan Gathers No Moss,” Sept. 29, and "Wet Spot" in "The Guppy Chronicles, Jan. 24.")

Royal Museum of British Columbia, Victoria, B.C.: The First Peoples Gallery includes the

transplanted home of Jonathan Hunt, a Kwakwaka'wakw chief from Tsaxis (Fort Rupert) Other exhibits show the imaginative masks of the Haida, a tribe nearly extinguished by smallpox. Totem poles grow among the flowers (at left).

transplanted home of Jonathan Hunt, a Kwakwaka'wakw chief from Tsaxis (Fort Rupert) Other exhibits show the imaginative masks of the Haida, a tribe nearly extinguished by smallpox. Totem poles grow among the flowers (at left).(See “Darth Vader Plays the Fiddle,” Oct. 2)

University of Montana, Missoula: Lynn’s parents met in the late 1920s at the university where in 1956 he spent half a year on the GI Bill before returning to California. It looks pretty much the same, although the city has blossomed with new subdivisions, population growth and a welcoming attitude toward writers. In any of the coffee shops, expect to stand in line behind at least two novelists, an unpublished poet and a laid-off newspaperman. At the university, we saw a traveling exhibit of Pulitzer Prize photos. Included was a great shot by our colleague and friend, Kim Komenich, now teaching at San Jose State.

The Mission Range, St. Ignatius, Mont., and Flathead Lake, Polson, Mont.: This spectacular range (below) is north of Missoula. We stopped to gaze. Then we came to Flathead Lake, which at 30-by-60 miles is half the size of San Francisco Bay, bigger than

Lake Tahoe and not nearly so crowded. Sheltered by the Mission Range, the area’s climate is just right for cherry orchards on the east and grape vines on the west.

Lake Tahoe and not nearly so crowded. Sheltered by the Mission Range, the area’s climate is just right for cherry orchards on the east and grape vines on the west.Corvallis, Mont.: Lynn’s mother, Melda Schwab Ludlow, is buried in the Corvallis cemetery along with her father, stepmother and other relatives. It’s situated in the foothills of the Sapphire Range and looks down at the Bitterroot Valley where her son was born in the Schwab farmhouse.

(For all three, see “The Montana Ludlow Legacy Tour,” Oct. 7)

Big Hole National Battlefield (National Park Service), Wisdom, Mont.: Unlike the Civil War battlefields crowded with monuments to the slain, the scene is much the same as it would have appeared in 1877. The Nez Perce warriors, still asleep when the 7th Infantry hit their camp and killed many families in their burning teepees, fought back with such ferocity that the soldiers retreated with heavy losses and cowered in rifle pits until it was safe. Col. John Gibbon called the battle a victory.

Gibbonsville, Idaho: Named for the boastful colonel at Big Hole. A boomtown in the 1890s before the silver mines played out, the hamlet was the home town of Lynn’s grandmother, Lillian Hull Schwab.

U.S. Highway 93 in Idaho: No Regret, Mt. Corruption, the Riddler and, at 11,850 feet, the

Devil’s Bedstead. Some of the West’s most beautiful mountains overlook this road with some of the West’s most memorable names. Starting with the Salmon River Scenic Bypass, the highway heads south between the Sawtooths on the west and the Lost River Range on the east. More than 100 peaks in Idaho are higher than 11,000 feet. From U.S. 93 we could see Borah Peak, named for the isolationist senator. At 12,668 feet, he looms over the Lost River Valley. (We couldn’t see the river because, of course, it had gone underground. After 100 miles under the lava beds, it percolates upward as springs below Twin Falls and flows into the Snake.)

Devil’s Bedstead. Some of the West’s most beautiful mountains overlook this road with some of the West’s most memorable names. Starting with the Salmon River Scenic Bypass, the highway heads south between the Sawtooths on the west and the Lost River Range on the east. More than 100 peaks in Idaho are higher than 11,000 feet. From U.S. 93 we could see Borah Peak, named for the isolationist senator. At 12,668 feet, he looms over the Lost River Valley. (We couldn’t see the river because, of course, it had gone underground. After 100 miles under the lava beds, it percolates upward as springs below Twin Falls and flows into the Snake.)Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve (National Park Service), near Arco, Idaho: If the surface of the moon is anything like this park, tell the astronauts to drop you instead in Kauai.

(For all four, see “The Indian Hater,” Oct. 10)

Dinosaur National Monument (National Park Service) near Jensen, Utah.: Forget the fossils. (View from the campground, at right.) Enjoy the palette of red, orange and beige rocks in shapes arranged by Mother Nature the Artist along the Green River – which is really green. Just outside the park we saw hundreds of sandhill cranes snacking in a newly mown field of corn.

Dinosaur National Monument (National Park Service) near Jensen, Utah.: Forget the fossils. (View from the campground, at right.) Enjoy the palette of red, orange and beige rocks in shapes arranged by Mother Nature the Artist along the Green River – which is really green. Just outside the park we saw hundreds of sandhill cranes snacking in a newly mown field of corn.(See “Old Bones,” Oct. 12, and "The Guppy Chronicles," Jan. 24.)

Frasier Meadows, Boulder, Colo.: It lacks meadows, but almost everything else is available at this not-for-profit retirement community where Rebekka Struik, Margo’s mother, is now a resident. She likes it. More than 250 clubs, committees, social and recreational activities are available for lifetime members in apartments for independent living and separate centers for assisted living, skilled nursing and hospice care. We stayed two nights in one of the guest apartments, ate well in the in-house dining rooms and met some of Rebekka’s friends. Some, like her, are retired professors. Several others are old friends from her many years in Boulder. She has abundant opportunities to pursue her activism for progressive issues.

(See “Pine Beetles,” Oct. 15)

Red Cloud, Neb.: Hometown of Willa Cather.

Her family's home (at right). Her bedroom.

Her family's home (at right). Her bedroom.Polk Progress, Polk, Neb.: We visited the late Norris Alfred’s now-shuttered print shop.

Platte River, near Central City, Neb.: We saw prairie falcons on Alfred’s “birding road.”

(For all three, see “Progress to Polk,” Oct. 18.)

Poor Ralph, Polk, Neb.: Across the street from Alfred's print shop, we found his former columnist, Marsha Redman and her husband, Ralph.

International Quilt Study Center and Museum, Lincoln, Neb.: It’s the world’s largest collection: More than 2,300 quilts. Plus a “virtual gallery” of 800 quilts that have been digitized and displayed on a big screen.

International Quilt Study Center and Museum, Lincoln, Neb.: It’s the world’s largest collection: More than 2,300 quilts. Plus a “virtual gallery” of 800 quilts that have been digitized and displayed on a big screen.(For both, see “Quiltish,” Oct. 19)

Sauk Centre, Minn.: Hometown of Sinclair Lewis and "Main Street." His home. The cemetery. His job at 17.

Bemidji, Minn.: Alleged home of alleged Paul Bunyan and alleged Babe the Blue Ox, both memorialized with wooden statues.

(For both, see “The Mainstreeters,” Oct. 23, and "The Guppy Chronicles," Jan. 24.)

Ishpeming, Mich.: We found the former home and department store built 100 years ago by Lynn’s great-grandfather, Frederick Braastad.

(See “Oberlin and Ishpeming,” Oct. 28)

Saugatuck, Mich.: Art Lane, alumnus of the late, great Champaign-Urbana Courier, proved that owning and editing a small-town newspaper can be immensely satisfying.

(See “The Carmel of Lake Michigan,” Oct. 29)

Oberlin, Ohio: We found Kenny and her roommates and her friends from San Francisco. Lynn asked each, “How do you like Oberlin College?” All gave the same answer: “I love it.” We stayed in the Victorian home of Maryann and Clyde Hohn. We played a few tunes with Clyde (at right, Kenny, Lynn, Anabel Hirano). Because the town could be taken for Bedford Falls, we expected to see Jimmy Stewart and Donna Reed strolling down sidewalks warmed by autumn’s yellow-red maple leaves.

(See “Oberlin and Ishpeming,” Oct. 28)

Niagara Falls, N.Y., and Niagara Falls, Ont.: This would be one of the rare occasions when clichés are apt. The waterfall is awesome. Totally. It's the bomb, doozy, cat's pajamas. Blew us away. Whatever. On the Canada side, the vision is corrupted by a helter-skelter amusement district with rides, cotton candy and schlock curiosities.

Lundy’s Lane Historical Museum, Niagara Falls, Ont.: Just up the hill from Niagara Falls in Canada, the Battle of Lundy’s Lane in 1814 was one of most vicious in the War of 1812 (or, as the Brits say, the Anglo-American War) It wound up with heavy casualties and a standoff between U.S. forces and British regulars with Canadian militias. As a strategic victory for the redcoats, it put an end to invasions of Canada by the U.S. The Canadians celebrate the battle, which today is all but forgotten in the U.S. We celebrate instead the Battle of New Orleans a year later. It put an end to invasions of the U.S. by Britain, where today it’s all but forgotten. At Lundy’s Lane, the history is interesting; the little museum is pretty lame.

(For both, see “Niagara Falls,” Oct. 30, and "The Guppy Chronicles," Jan. 24)

George Eastman House and International Museum of Photography of Film, Rochester, N.Y.: As you would expect, the museum holds one of the world’s best collections of Brownies, Kodaks, Instamatics, Speed-Graphics, an Edison Kinetoscope, a daguerreotype outfit, an 18th century camera obscura etc. etc. Margo took a look at the palatial 37-room mansion of the bachelor founder of Eastman Kodak Company.

Erie Canal, New York: We climbed the “Flight of Five” locks at Lockport, N.Y., and visited “Long Level” near Syracuse, N.Y., where Ann and Dale Tussing live in the historical ambience of their 200-year-old house.

Walden Pond, Concord, Mass.: We walked around the little lake, its glassy surface broken by a rowboat. Would a boat intrude on the reflections of Henry David Thoreau?

Walden Pond, Concord, Mass.: We walked around the little lake, its glassy surface broken by a rowboat. Would a boat intrude on the reflections of Henry David Thoreau?The Semitic Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.: This fascinating array of exhibits from the ancient Near East includes a glimpse of the forgotten civilization of the Hurrians. The free museum’s chief exhibit is a life-size reproduction of an Iron Age home in ancient Israel, a “pillared” house of mud bricks over a stable.

(For all four, see “The Big Stone House,” Nov. 2)

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (National Park) in Hyde Park, N.Y., near Poughkeepsie. Margo hiked up to Val-Kill, the country retreat now open as the Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site. We saw the typescript of FDR’s message to Congress on Dec. 7, 1941, in which he took a pencil to the unremarkable opening line –“a date which will live in world history” and changed it, memorably, to “a date which will live in infamy.” Wow.

Walkway Across the Hudson, Poughkeepsie, N.Y. : No longer a railroad bridge, it spans the river as a perch for hikers and falcons.

(For all three, see “First Lady of the World,” Nov. 6)

New York, N.Y.: Our explorations included the Main Public Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Grand Central Station, New York Times newsroom, New York Daily News newsroom and the cold but fascinating sidewalks of New York.

Liberty State Park, Jersey City, N.J.: Originally sloughs and then oyster beds, the tideflats had been filled for railroad yards that turned into toxic brownfields. The state of New Jersey began to reclaim the wastelands in 1976 for a 1,200-acre park with bike paths, walkways, a golf course, science center and the Statue of Liberty overlook. As Margo and Dan North inspected the birdlife, we reflected on the possibilities of a landscape ruined by industry, the military and neglect.

(For both, see “Not-a-New Yorker Muses on the Big Apple,” Nov. 18, and “Escape from New York,” Nov. 13, and "Antiques Roadshow" in "The Guppy Chronicles," Jan. 24")

Dover, Del.: The Green’s carefully preserved buildings illustrate the history documented in the nearby Delaware Public Archives.

(See “Not-a-New Yorker Muses on the Big Apple,” Nov. 18)

Washington, D.C.: Margo visited the Smithsonian Institute’s array of museums (Air and Space, American Art, the Freer and Hirshhorn galleries, African Art, American Indian Art, American History, the National Portrait Gallery) She looked at the White House (from outside) Lynn emerged from his sick bed to wander through the National Museum of American History, which may account for his grumpy comments about Dumbo. We had the opportunity to tread sidewalks trembling with emanations of power.

(See “A Hick in Washington,” Nov. 21, and "The Guppy Chronicles," Jan. 24")

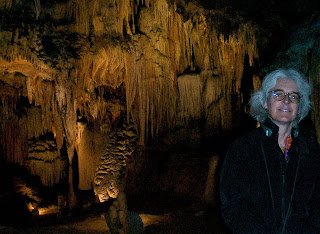

Luray Caverns, off Skyline Drive, near New Market, Va.: Proprietors of this for-profit natural wonder aren’t content with spectacular wonders like Saracen’s Tent (a translucent drapery of flowstone), Titania’s Veil (a stalagmite of crystalline dripstone) and the Washing Well (a 6-foot pool with a mirror surface broken only by the splash of coins for charity)

They have added a golf course, a wonderful vintage car museum, a one-acre maze of hedges, a carillon tower and miles of hiking trails. With other tourists, we heard music from the Great Stalacpipe Organ. The console, sort of a player piano untouched by human hands, is wired to little rubber-tipped mallets. They tap dozens of stalactites with just the right resonance. It sounds like the ultimate basso aria in an opera for whalefish, a cross between a sousaphone and Harry Partch’s marimba eroica. We learned that it takes 120 years, according to the geologists, for drips to form just one cubic inch atop a stalactite. At Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico, where nobody is allowed to touch anything, the rangers must shudder when told about the Luray’s bonus attraction. They might even stop dusting for lint.

They have added a golf course, a wonderful vintage car museum, a one-acre maze of hedges, a carillon tower and miles of hiking trails. With other tourists, we heard music from the Great Stalacpipe Organ. The console, sort of a player piano untouched by human hands, is wired to little rubber-tipped mallets. They tap dozens of stalactites with just the right resonance. It sounds like the ultimate basso aria in an opera for whalefish, a cross between a sousaphone and Harry Partch’s marimba eroica. We learned that it takes 120 years, according to the geologists, for drips to form just one cubic inch atop a stalactite. At Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico, where nobody is allowed to touch anything, the rangers must shudder when told about the Luray’s bonus attraction. They might even stop dusting for lint.(Unblogged)

Blue Ridge Parkway (National Parks), western Virginia: After a hundred miles of the same scenery, we cut over to the Interstate (U.S. 95). We don’t remember anything. This highway could be anywhere. (At left, a Fern Bar.) Next time we’ll try to see the back roads of Tennessee.

Blue Ridge Parkway (National Parks), western Virginia: After a hundred miles of the same scenery, we cut over to the Interstate (U.S. 95). We don’t remember anything. This highway could be anywhere. (At left, a Fern Bar.) Next time we’ll try to see the back roads of Tennessee. (See “Heading Home,” Nov. 21)

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, Nashville, Tenn.: We live in a world where Conway Twitty gets more gold-plated status than Michael Tilson Thomas or Bix Beiderbecke, but this gilded shrine to the accomplishments of public relations is a lot more entertaining than, say, an afternoon in Costco.

(See “Nashville Dreams,” Nov. 25, and "Beaten to the Punchline" in "The Guppy Chronicles," Jan. 24")

Madisonville, Ky.: The sign called it “The Best Town on Earth.” We hurried past Innovative Hair Design and the Giggles and Grins consignment shop.

We had been urged to buy lunch across from the courthouse at the Dinky Diner. It was dinky enough but, sadly, closed that day.

We had been urged to buy lunch across from the courthouse at the Dinky Diner. It was dinky enough but, sadly, closed that day.National Quilt Museum, Paducah, Ky.: Billed as a “portal to contemporary quilt experience through traditional and non-traditional quilt exhibits and quilt workshops.” Three galleries. Until 2008, it was the museum of the American Quilters Society.

New Madrid, Mo.: The site of the nation’s worst recorded earthquake back in 1815, the Mississippi River town gets no respect. No tourists. No hotels. No cable cars.

(For all three, see “Palooka from Paducah,” Nov. 30)

Walton 5 & 10 and Wal-Mart Visitors Center, Town Square, Bentonville, Ark.: In a canyon a few blocks from the tidy Town Square, cranes and construction crews are building the $400 million Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. It’s a hobby of Alice Walton, the billionaire daughter of Wal-Mart’s founder, Sam Walton. She lives near Dallas, Texas. Strangely, only two other people were visiting Sam Walton’s first store, a museum and shrine. (We never saw a Wal-Mart that didn’t have parking lots crowded with cars. We ventured inside only once – to use the lavatory – but took note of all the happy shoppers who might otherwise have been buying stuff in the vanished haberdasheries, shoe stores and dress shops in downtowns that are now, in a word, kaput.)

(See “Mister Walton’s Store,” Dec. 7)

Hot Springs National Park (National Park Service), Hot Springs, Ark.: They call it The Golden Age of Bathing, when eight luxurious bathhouses pampered men and women in what the park historians call “an era of leisure and grace.” It’s not likely that John Muir would have regarded Bathhouse Row as the equivalent of Yosemite and Yellowstone, but in 1921 it became a national park. When people stopped coming, the great bathhouses fell into disrepair, leaving only the Buckstaff in operation. The Park Service is now restoring the others, but not necessarily as temples of curative waters. The Quapaw reopened in 2008 as a bathhouse, but the Ozark is to be an art museum. We walked through the Fordyce, the park visitor center. We found a museum of empty bathtubs, massage tables, hydrotherapy gear and a billiard table, not exactly what the Sierra Club envisioned.

Notable: The Park Service’s only public campground, in nearby Gulpa Gorge ($10), doesn’t have showers or water hookups. That’s odd. The 47 springs produce about 700,000 gallons of hot water every day for the bathhouses and fountains in a resort with too many innkeepers and too few tourists. It’s a mystery. Not really.

(Unblogged: We didn’t write a report on Hot Springs or the next item, the Cabildo.)

The Cabildo: Louisiana State Museum., the French Quarter, New Orleans, La.: The scene of the Louisiana Purchase ceremonies in 1803, the Cabildo kept

us until closing time with fascinating exhibits, historical paintings and well-written background statements.

us until closing time with fascinating exhibits, historical paintings and well-written background statements.Café Du Monde, New Orleans: Like other tourists, we stopped for beignets and coffee. The obligatory street band (black and white with a Vietnamese trombonist) tuned up on the sidewalk while we brushed away the powdered sugar. The buskers told the obligatory jokes and performed the obligatory tune about the saints. They were pretty bad. In their humble way, the musicians showed why trad jazz, even its birthplace, is as dead as Jelly Roll Morton. Entertainment: B minus. Jazz: F.

(See “We Didn’t Learn Our Lesson,” Dec. 5)

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans: Four years after Hurricane Katrina brought catastrophic flooding, we saw scores of houses still unoccupied and many a vacant lot where people once lived in their own homes. The issues of rebuilding and blame are too complex for us to discuss intelligently, but even a tourist can be appalled at the evidence of boondoggling at every level of government.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans: Four years after Hurricane Katrina brought catastrophic flooding, we saw scores of houses still unoccupied and many a vacant lot where people once lived in their own homes. The issues of rebuilding and blame are too complex for us to discuss intelligently, but even a tourist can be appalled at the evidence of boondoggling at every level of government. (See notes and photos at the end of “Mister Walton’s Store,” Dec. 7)

Acadian Culture Center (National Park Service), Lafayette, La.: It’s one of six sites of the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. Missing from our schoolbooks: In Nova Scotia, cruel British and rapacious New Englanders in the mid-18th century expelled about 20,000 prosperous French-speaking Acadians, burned their communities, crammed thousands into pesthole ships (thousands perished) and scattered the broken families throughout the colonies, Canada and France. As the new planters stole farms and fisheries, they of course bad-mouthed their victims. Many survivors were welcomed in the former French colony of Louisiana, where the Acadians came to be known as Cajuns.

(See "Long Waltz Across Texas," Dec. 8)

Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, Austin, Texas: In spite of giving the impression that Texas and the Confederacy won the Civil War, this well-organized museum helps visitors with imaginative displays, useful timelines and vivid biographical sketches.

Joyce Gross Quilt History Collection (currently seen at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, Austin): Put together over the years by a woman in Mill Valley, her collection and library somehow wound up at the Center for American History at the University of Texas. More than 170 quilts and hundreds of written materials document the history of quilting in 20th century America.

(For both, see “Austin City Limits,” Dec. 12)

Roadrunner, Fort Stockton, Texas: A dinosaur-sized statue of the cartoon character greets motorists.

(See “Race Across the Desert,” Dec. 16)

Carlsbad Caverns National Park (National Park Service), Carlsbad, N.M.: In a word: Unforgettable.

(See “Carlsbad Caverns,” Dec. 14)

London Bridge, Lake Havasu City, Ariz.: We saw an artificial span on an artificial canal next to an artificial lake.

(See “A Tale of Two Cities,” Dec. 23)

Ludlow, Calif.: A mini-hamlet on old Route 66 in the Mojave Desert.

(See “Race Across the Desert,” Dec. 16, "The Castle and the Ghost Town," Jan. 25, and "The Guppy Chronicles," Jan. 24)

California Valley, near Bakersfield, Calif.: A 7,500-acre scam.

(See “A Tale of Two Cities,” Dec. 23)

The Cities – Small and Large – We Visited

Oroville (Calif.); Medford, Bend, Portland and Astoria (Ore.); Vancouver, Olympia and Port

Angeles (Wash.); Victoria (B.C.); Missoula (Mont.); Salt Lake City (Utah);

Angeles (Wash.); Victoria (B.C.); Missoula (Mont.); Salt Lake City (Utah); Boulder (Colo.); Red Cloud, Lincoln, Polk and Brownville (Neb.); Des Moines and Boone (Iowa); Sauk Centre, Gully and Bemidji (Minn.); Appleton (Wis.); Ishpeming and Saugatuck (Mich.); Oberlin (Ohio); Niagara Falls (Ontario); Rochester, Lockport, Niagara Falls, Syracuse, Pleasant Valley, Poughkeepsie and New York City (N.Y.); Boston (Mass.); Jersey City (N.J.); Dover (Del.); Washington (D.C.); Nashville (Tenn.); Maddisonville and Paducah (Ky.); Rogers, Fayetteville, Bentonville and Pine Bluff (Ark.); New Orleans, Algiers, and Lafayette (La.); Austin and Pecos (Texas); Carlsbad and Deming (N.M.); Sun City and Lake Havasu City (Ariz.); Ludlow, Buttonwillow and California Valley (Calif.).

Boulder (Colo.); Red Cloud, Lincoln, Polk and Brownville (Neb.); Des Moines and Boone (Iowa); Sauk Centre, Gully and Bemidji (Minn.); Appleton (Wis.); Ishpeming and Saugatuck (Mich.); Oberlin (Ohio); Niagara Falls (Ontario); Rochester, Lockport, Niagara Falls, Syracuse, Pleasant Valley, Poughkeepsie and New York City (N.Y.); Boston (Mass.); Jersey City (N.J.); Dover (Del.); Washington (D.C.); Nashville (Tenn.); Maddisonville and Paducah (Ky.); Rogers, Fayetteville, Bentonville and Pine Bluff (Ark.); New Orleans, Algiers, and Lafayette (La.); Austin and Pecos (Texas); Carlsbad and Deming (N.M.); Sun City and Lake Havasu City (Ariz.); Ludlow, Buttonwillow and California Valley (Calif.).